First Nations Chief George Lepine resurrected and codified the traditional Plains Cree martial art of okichitaw using customs and techniques of the past to make Indigenous nations stronger for the future.

Whether it’s Shaolin monks flying through the air, Japanese karate masters spinning out roundhouse kicks, or action ace Jackie Chan doing his own impressive stunts onscreen, in the minds of most people, the martial arts conjure images of Asia. With the notable exception of the ’70s TV western Kung Fu, starring David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine dispensing spiritual wisdom and fighting for justice in the Old West, the confluence of cowboys and martial arts is seemingly rare and remote. How much less anything Native or First Nations?

Most people’s exposure to Indigenous warfare and fighting techniques comes in all probability from movies such as Last of the Mohicans or Dances With Wolves. One man, however, is changing all that.

For more than 40 years, Okimakahn Chief George J. Lepine has been researching, redeveloping, and teaching the only achievement-based Indigenous martial art in Canada. Welcome to okichitaw.

Growing up around Winnipeg in southern Manitoba, immersed in the tales and traditions of his Plains Cree, Assiniboine, and Métis heritage, Lepine developed a keen interest in the combat arts of his people at the impressionable age of 12. He likes to tell a story about an experience from his boyhood that gave birth to this passion and set him on the life path of a martial artist.

“I still recall an experience I had as a young boy with my Uncle Ted,” Lepine says. “As we walked along the shores of Lake Manitoba, I listened to him talk about how we would use birch bark for making canoes and containers as he pointed to the birch trees along the shoreline. Suddenly, he stopped and picked up a piece of driftwood. He glanced over at me and said, ‘It looks just like a mistik doesn’t it, Georgie?’ He obviously saw the puzzled look on my face. So, he crouched down, placed the driftwood on the sand, and used a twig to trace lines around the wood. He started to tell me about this Native weapon and how it visually resembled a rifle stock. He said that it was common to see our ancestors with it, sometimes in ceremony or dancing, but it was primarily used in war. He explained that the weapon was usually dressed or personalized in some way, pointing out where this would be done on the weapon. I still recall him tracing where the spike would have been installed on the outside elbow and showing me where we would place brass tacks along the handle. He said the full name of the weapon in Plains Cree was notini-towin-mistik — the gunstock war club. He continued to explain the angles and parts of the mistik, how the weapon was made, what kind of wood we used, how we added the metal spike, and the different ways it could be used to strike.”

By 17, Chief George’s desire to learn more about martial arts led him to search outside what his family could teach him. This presented a challenge, however, as all the other systems were foreign. He moved from Western boxing to Eastern martial arts such as judo, hapkido, and taekwondo. Yet, something always drew him back to the fighting methods he learned from his father and his uncles as a young boy.

Returning to the roots of his First Nations heritage, Lepine threw himself into research determined to reclaim and resurrect the centuries-old combat tactics and weapons applications of his people. He traversed North America, finding resources hidden everywhere from “small libraries in the middle of nowhere to the National Archives of Canada.” He also conducted countless hours of interviews with elders, teachers, and keepers of knowledge to ensure that what he was creating would be as authentic as it was effective.

“Many of these people who I have spoken with are the cornerstone of our culture,” Lepine says. “They are the keepers and teachers of our history and traditions. ... Without their wisdom, experience, advice, and guidance, okichitaw would not have become what it is today.”

Through his decades-long studies of the history, various battle tactics, and weaponry of the First Nations, he gained invaluable and extensive knowledge of the culture surrounding Indigenous warrior societies. “Historically, the men of these groups had various duties which included providing for those in need and protecting women, children, and the elderly,” Lepine says. “They also policed any buffalo hunts and guarded valuables in the community. These were the men who enforced the laws and were greatly respected as a result of their personal commitment and dedication. They had to give up material possessions willingly, never be jealous or envious of anyone, and always take immediate action in dealing with a serious task without question, much like a modern-day soldier. ... Participation in any of these types of units was to gain something on a personal level: prestige, honor, wealth, and respect from others, even their enemies.”

According to Lepine, the word okichitaw (pronounced oh-kee-chee-taw) is derived from several Plains Cree words that refer to these Indigenous warrior societies, called “The Warriors” and “The Worthy Young Men” in Cree. It is intended to signify the modern individual who has chosen to follow the way of the warrior. The term was provided to him after much discussion with traditional knowledge keepers. “They felt that the martial arts system’s name not only had to stand for the fighting structure, but it also had to embrace the teachings of [the] Indigenous lifestyle,” Lepine explains.

Okichitaw is indisputably a hard martial art, meaning it meets the attacks of an opponent with strategically applied force in return. Chief George notes that, in the past, combat on the open plains usually produced lethal results. Of course, the application of deadly force would not be acceptable in a modern context, so a structured and disciplined approach had to be established if these techniques were to be preserved and taught. To codify okichitaw in a nonlethal form, Lepine turned to his studies and experience in other martial arts.

“Combining my Indigenous heritage through extensive combative research as well as my thorough knowledge of martial arts allowed me to bring everything together to assist me on this path,” he says. “Okichitaw is now a form of martial arts which has an achievement process for participants and students who want to attain rank.” Nonetheless, okichitaw maintains a fast-paced, no-nonsense approach to fighting. When facing an assault from an enemy, students are taught how to end the momentum of the opponent, bring them to the ground, “finish them out,” and quickly move on to the next engagement or challenge.

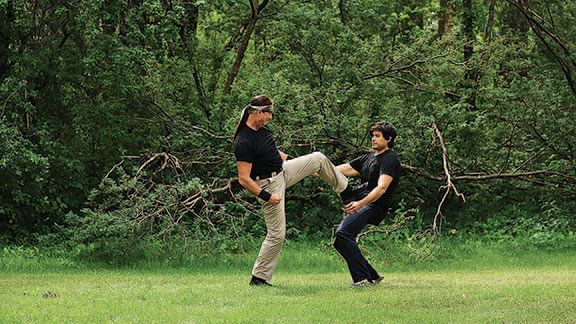

Lepine makes clear that okichitaw is not only taught in the studio like other martial arts, but also outdoors, regardless of weather conditions. This quite intentional choice to train in Mother Nature involves far more than the mundane logistics of acquiring extra practice space. In fact, the major factor distinguishing okichitaw from most other systems, Lepine emphasizes, is its connection to the land. As an example, he notes that, historically, there was significant difference between Indigenous combat that occurred on the open plains versus that of the woodlands. “In the application of battle techniques in open space, speed and concealment are a factor. In a wooded area, sound and accuracy have more impact on combat engagement. ... The environment and weather always played heavily on a warrior’s actions and techniques. Understanding both of these could mean the difference between success and failure.” Accordingly, to maintain historical authenticity, students of okichitaw are encouraged to cultivate comfort and proficiency in applying effective martial arts techniques in any environment and on any kind of terrain.

Combining my Indigenous heritage through extensive combative research as well as my thorough knowledge of martial arts allowed me to bring everything together to assist me on this path.

In addition to hand-to-hand applications, okichitaw also provides its students with training in traditional Plains Cree weaponry. This includes the knife, the tomahawk, the short lance, and the gunstock war club, each of which has specific throwing applications. “My favorite?” Lepine says. “Well, my favorite weapon is usually the one I’m holding at the time I’m using it!”

Much of the movements employed in the use of the weapons translate fluidly to empty-hand applications. This is how many of the empty-hand strikes in the art were derived. “If you think about it, almost all other forms of hand-to-hand martial arts and their respective movements are directly related to the historical weapons that were a part of that particular martial arts’ history,” Lepine explains. “Okichitaw is no different. Having said that, I would say that we teach the concept[s] of okichitaw with much more rigidness than many other martial arts systems to ensure that we preserve our historical approach.”

That historical approach permeates every teaching session in okichitaw. It is not just another martial art with some unusual applications and weapons. It is an immersion experience in First Nations culture, language, history, and traditions.

“I have maintained very strict discipline and methods in teaching okichitaw to ensure that it doesn’t get influenced by other martial arts,” Lepine says. “The techniques, the use of bushcraft, our weaponry, our educational understanding of using the environment for effective battle engagement is paramount. I have developed okichitaw’s training programs and curriculums to embrace an Indigenous perspective by following our traditional practices through self-defense and warfare tactics. It is important that I ensure that cultural practices are always a part of classes. This is done through powwow dance style workouts, speaking traditional language when giving commands, learning about the weaponry and tactics, participation in matotison [sweat lodge] ceremony, and openly sharing various aspects of Indigenous knowledge.”

Through the intensity of it all, Chief George constantly reminds his students of okichitaw’s primary imperative goal: that the training lead them to truly become “warriors of peace.”

“One of my uncles would say that you gain your wisdom through pain and suffering,” Lepine says. “Although physical pain may be a part of it, this also includes emotional and spiritual pain as well. I believe that the true embodiment of being a warrior of peace is gained through the collection of our own personal experiences through difficulty and struggle. All creatures go through this — we are no different. In okichitaw, we provide mentoring, martial arts training and discipline so that a person learns to carry themselves with humility and fearlessness, but I also want to make sure that when students are learning this, they remain compassionate and knowledgeable to the world that surrounds them. I teach my students that a true warrior of peace does not necessarily mean to only fight for themselves, but rather for their family and community.”

Chief George has witnessed firsthand the tremendous benefits to his students that okichitaw provides. “In okichitaw, we believe that the harder you train your body the more you will grow spiritually,” he says. “In these difficult times, okichitaw is an intelligent and effective way to prepare people to deal with today’s challenges. It provides a means through which our students can deal with conflict, whether it’s personal or from an outside source. It’s not only an excellent form of physical conditioning or an exciting and challenging recreational way to enhance agility — it provides an ethical approach to conflict resolution.”

I teach my students that a true warrior of peace does not necessarily mean to only fight for themselves, but rather for their family and community.

With physical skills as a base, okichitaw practitioners develop the confidence to use psychological and social self-defense skills that enable them to deal with the fears and challenges of everyday life while at the same time learning traditional Indigenous ways and teachings to further their spiritual and cultural awareness. “I think the greatest lifesaving action I’ve seen okichitaw training achieve is to help people heal from the interpersonal trauma that affects our community,” Lepine says.

The physical activities he teaches in okichitaw enhance mental conditioning, which in turn help develop a positive self-image and personal self-worth through the expression of Indigenous identity. “Our youth have great challenges nowadays,” he says. “It is well-known that Indigenous youth have twice the national average of suicide, and it’s three times that on First Nations reserves. I can safely say that okichitaw helps prevent and deter the greatest threat to our Indigenous community – suicide. For all of us to be successful, Indigenous people need access to culturally relevant activities like okichitaw to help overcome intergenerational trauma and assist in the prevention of suicide among our youth.”

Living the Indigenous way, as Chief George does, allows him to reflect the teachings, tactics, and movements of his ancestors and truly honor his past. “Since the start of my journey, many of my family members who first taught me the martial ways of my Indigenous ancestors have departed,” he says. “I am now the last one remaining who knows these teachings, so it is so very important that I continue to share this knowledge through okichitaw to ensure that our contributions and stories will never be forgotten.”

Lepine’s lifelong interest in and commitment to developing a structured concept for Indigenous battle tactics, methods, and history has allowed okichitaw to be brought back into modern society as an effective achievement-based martial art. For Chief George Lepine, it’s a feat of preserving the past with an all-important forward-looking purpose: “The motto that I use in describing what okichitaw does for our people is this: We use the traditions and techniques of our past to make our Nations stronger for the future.”

To find out more about okichitaw and Chief George Lepine’s teaching, visit okichitaw.com.

From our May/June 2022 issue

Photography: (Okichitaw) Sarah Koehn/Courtesy Native Canadian Centre of Toronto; (All others) Lina Lepine/Courtesy Native Canadian Centre of Toronto