Throughout American history, the men occupying the highest office in the land have looked west to the future.

While campaigning for the presidential election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln was asked to write a pair of autobiographical sketches for voter information. In recalling a childhood spent in “a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals, still in the woods” and how as a 21-year-old he’d helped his family relocate from Indiana to Illinois by driving an ox-drawn wagon, Lincoln wasn’t simply reciting the dry facts of his life. He was tapping into a mythology that had long powered the American presidency.

Westward expansion, frontier moxie, the lure of the wild, and a spirit of self-sufficiency drove America’s political vision of itself throughout the 19th century. Protecting, expanding, and enhancing that vision has defined it ever since. Each U.S. president has had a special relationship with the West. Each created policies and supported or opposed legislation that shaped it, for better and worse.

The West has never been an easy place. Viewed through a historical lens, failures in Western policies bedevil the reputations of many leaders. By crusading for and signing the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and for his connection to the subsequent Trail of Tears tragedy, Andrew Jackson left a tarnished legacy.

Such painful episodes are difficult to confront. But contemporary reassessment of history doesn’t negate the achievements of the men who embraced the promise of the West with such vigor and vision that their standing as great “Western presidents” has made them an indelible part of the landscape, figuratively and literally. Without them, the West may still have been won, but it wouldn’t have evolved in such a uniquely American way.

Here are seven presidents who each had an especially big hand in building and shaping the West.

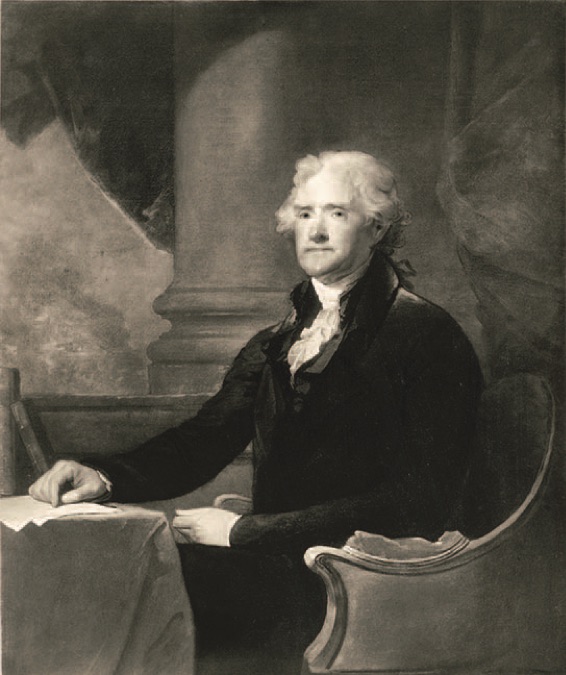

Thomas Jefferson, 1801—1809

When Thomas Jefferson approved the Louisiana Purchase — the official announcement came on July 4, 1803 — the United States acquired from France approximately 827,000 square miles stretching from the Mississippi River as far west as modern Montana. The size of the country doubled overnight, an administrative nightmare that might have frozen lesser men.

Jefferson remained composed as an eagle. In sending the Lewis and Clark-led Corps of Discovery to explore, survey, and map the territory in 1804 — and commissioning equally crucial missions such as Thomas Freeman’s 1806 Red River Expedition into the Southwest — he extended not just the physical boundaries but the mythic idea of the American West.

The son of a surveyor and mapmaker on the Virginia frontier, Jefferson romanticized the West and maintained a lifelong commitment to asserting American claims to Western lands. That commitment was not without problems. The man who revered Native Americans — he built an “Indian Hall” filled with artifacts at his Monticello estate — also laid the foundation for the destructive reservation system by setting aside Western lands for forcibly displaced Native peoples. When he claimed dominion in the name of the United States over the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, most or all of that land was under the control of Native American nations. What’s more, Jefferson fully understood this yet nevertheless asserted “right of purchase” claims upon Indigenous peoples.

“Jefferson appears both as the scholarly admirer of Indian character, archaeology and language and as the planner of cultural genocide, the architect of the removal policy, the surveyor of the Trail of Tears,” wrote Canadian-American anthropologist Anthony F.C. Wallace in an unflattering appraisal that’s nevertheless roughly shared by many historians regarding Jefferson’s record with Native Americans.

The history of the American frontier is filled with triumph and tragedy. Though he didn’t see the West himself and never personally ventured farther west than Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, Jefferson’s physical contributions to America’s westward expansion are nevertheless unsurpassed.

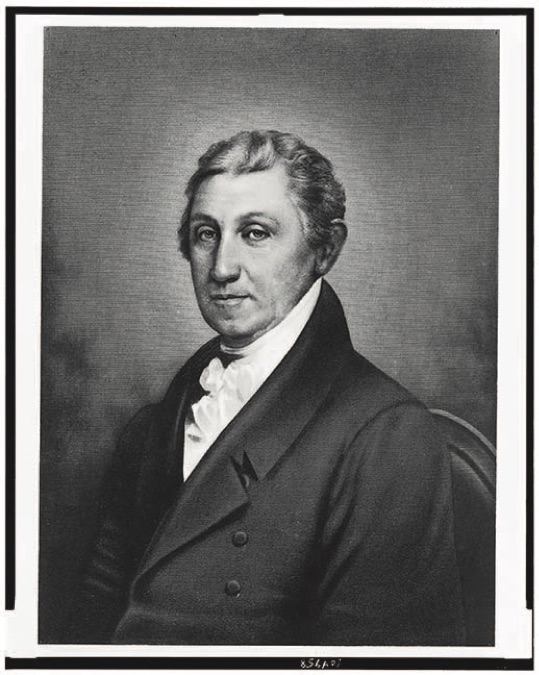

James Monroe, 1817—1825

As president, Thomas Jefferson receives credit for the Louisiana Purchase. But as Jefferson’s emissary to France, it was the future fifth president who, along with Minister to France Robert Livingston, negotiated the deal, and did so by the seat of his pants.

Monroe’s directive from Jefferson was simply to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans and West Florida for up to $10 million. Upon arriving in France, however, Monroe found the French nervous about a pending conflict with Great Britain and willing to sell their claim to far more territory for $15 million. Unable to communicate quickly with overlords at home, but tittering at the deal of a generation in front of them, Monroe and Livingston ignored orders and clinched the deal.

Leading a country surrounded by expansionist threats such as Spain, France, Great Britain, and Russia, President Monroe announced his Monroe Doctrine in an 1823 address to Congress, warning European powers that any further attempt to colonize lands in the Western Hemisphere would be seen as an act of hostility against the United States. It was mostly bravado. The young nation was incapable of backing up Monroe’s assertion of unilateral protection over the entire Western Hemisphere, and the implied threat was initially laughed off by European powers. As the nation grew, however, the Monroe Doctrine became the political cornerstone of America’s westward expansionism.

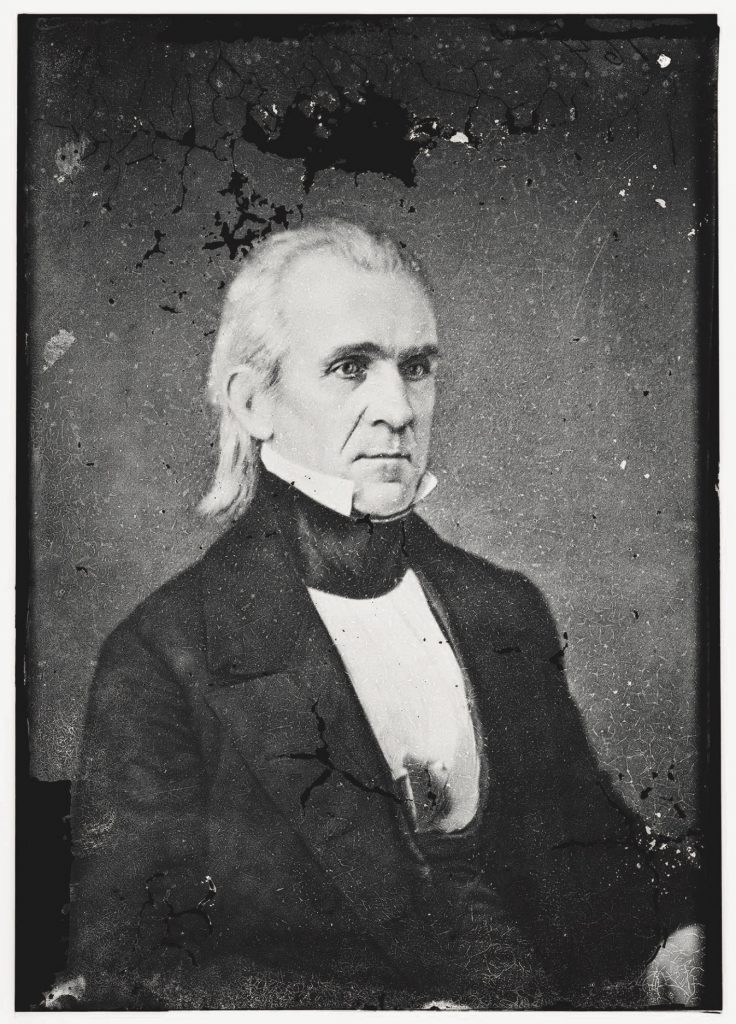

James Polk, 1845—1849

New York journalist John L. O’Sullivan may have coined the phrase Manifest Destiny in 1845 to describe America’s belief in a providential empire stretching from sea to shining sea, but no man is more associated with the zeal for westward expansion than President James K. Polk. Regarded as a dark-horse candidate in 1844, as president, Polk nevertheless “chose to ride boldly across a bright land and in doing so opened up the American West to half a century of unbridled expansion,” according to biographer Walter R. Borneman.

Did any one-term president do as much to enlarge the country’s future? Among the North Carolina native’s accomplishments were the annexation of the Oregon territory from Great Britain, which extended American land to the Pacific Ocean for the first time. As notable was the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which concluded the Mexican-American War with Mexico, ceding 525,000 square miles to the United States, including all or parts of present-day Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, thereby growing America’s territory by more than one-third. Mexico also gave up all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as America’s southern boundary. Historian H.W. Brands calls Polk “the most aggressively expansionist of all American presidents.”

Polk had long had his eye on the economic and strategic potential of California when, on December 5, 1848, his State of the Union address confirmed to the country that large amounts of gold had been discovered there: “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service who have visited the mineral district and derived the facts which they detail from personal observation.” The address sparked the Gold Rush, which in turn fueled westward expansion.

“Yet a change of just 5,000 votes in New York would have elected Henry Clay president instead,” wrote Borneman in Polk: The Man Who Transformed the Presidency and America. “Clay appeared content to let Texas remain independent and Oregon in British hands. How different the map of the United States might look today if that had happened.”

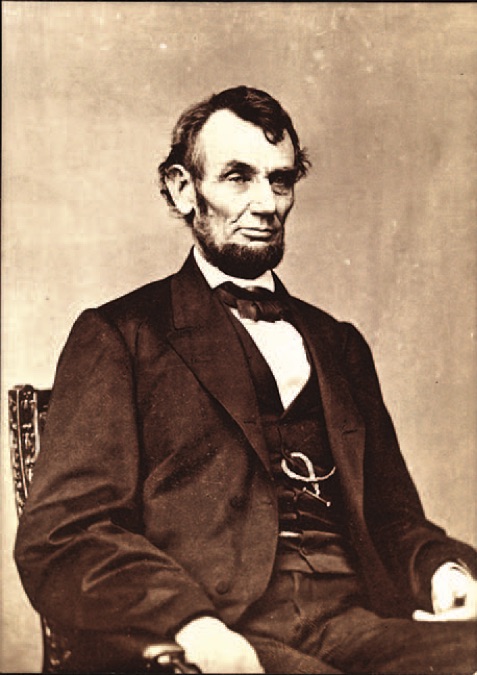

Abraham Lincoln, 1861—1865

The nation’s 16th president is known around the world for emancipating America’s slaves. But was the self-taught lawyer born in Kentucky also responsible for creating the cowboy mystique that would come to dominate the American West? In part, yes, according to two Western historians.

Lincoln was the last president to preside over a country predominantly oriented on a North-South axis. Yet even as he remained focused on the Civil War during his presidency, he never failed to promote the Western destiny he knew awaited the country.

While war raged, he found time to push through the Homestead Act (providing 160 acres to frontier settlers); establish the Department of Agriculture to oversee national land, farming, livestock, and forestry interest; and protect California’s Yosemite Valley by signing the Yosemite Land Grant Act.

Aside from preserving the union and abolishing slavery, Lincoln’s greatest contribution to the country may have been his ardent support of railroads. Including the landmark Union Pacific-Central Pacific railroad grant, he provided the largest federal subsidies in U.S. history to that point and made more Western lands available to railroads than any other president. Though he wouldn’t live to see the 1869 driving of the golden spike in Promontory, Utah, that completed the First Transcontinental Railroad — nor the 1867 purchase of Alaska from Russia, negotiations for which ran throughout his presidency — his rank as one of the greatest Western presidents was secured.

“Lincoln’s foresightedness, combined with the expansion of the railroads, stimulated western migration and tourism,” wrote Glenda Riley and Richard W. Etulain in Presidents Who Shaped the American West. “Railroads also encouraged the production of many consumer goods, especially cattle. Western ranchers who had driven their cattle over land routes to markets now drove them to railheads. ... In the process, the American cowboy emerged as the icon of the West.”

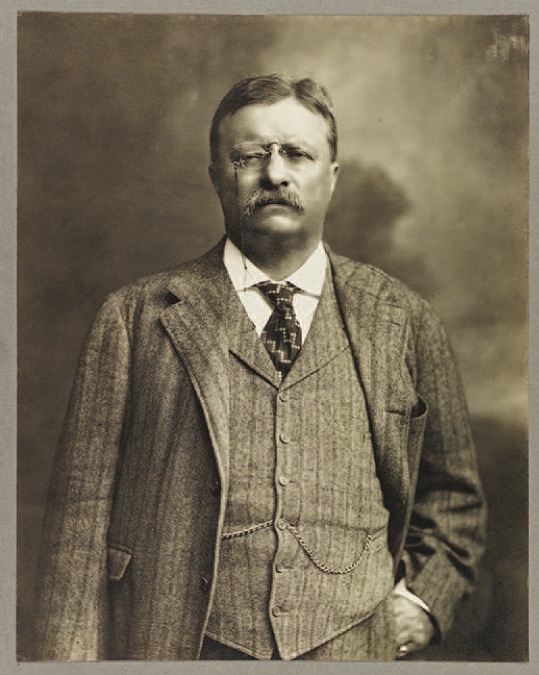

Theodore Roosevelt, 1901—1909

The West profoundly changed Theodore Roosevelt, and in return the native New Yorker profoundly changed the West. After the deaths of his first wife and mother in 1884, he retreated to his North Dakota ranch. “There he mastered his sorrow as he lived in the saddle, driving cattle, hunting big game — he even captured an outlaw,” according to the official White House history.

So thoroughly did the highborn Easterner transform himself into a burly Western outdoorsman that when he became president in 1901, Republican politician and coal and iron magnate Mark Hanna complained, “That damned cowboy is president now.”

Though alarmed at damage wrought on Western landscapes by unchecked development, the so-called “conservationist president” in fact danced between resource exploitation, management, and preservation. But conservation is his legacy. Under his administration, Roosevelt created the U.S. Forest Service and established 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, four national game preserves, five national parks, and 18 national monuments, and protected approximately 230 million acres of public land.

“Roosevelt expanded the western cowboy into a cowboy/soldier/hero who was a ‘real’ man — strong, courageous, individualistic, tough — and western,” wrote Riley and Etulain. “Almost single-handedly, with his author’s pen and charisma, he made the West and its manhood a national standard.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933—1945

Critics may argue that in bringing the full weight of federal governance beyond the Mississippi River, Franklin D. Roosevelt took the “Wild” out of the West. It was in the Depression-wracked expanses of the West, however, that FDR saw the best chance to regenerate America’s battered spirit. Besides, as Brands argues in Dreams of El Dorado: A History of the American West, nearly all Western states began life as federal territories: “The creation of the American West, as the American West, was arguably the greatest accomplishment in the history of the American federal government.”

Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps put 250,000 young men to work in the West carrying out reforestation, road-building, and flood-control programs. His Agricultural Adjustment Act revitalized farming and ranching, two of the West’s most important industries. His Public Works Administration built electricity-bringing dams across the West, including completion of the Boulder (Hoover) Dam on the Colorado River and Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River.

In the end, his New Deal programs for infrastructure in the West were as welcome as the transformation of Southern states brought by his equally dramatic Tennessee Valley Authority. Some have derisively called the changes Roosevelt wrought “Uncle Sam’s West.” In fact, most of his programs were enormously popular in Western states, where he swept every electoral vote in both the 1932 and 1936 elections.

“Western individualism sneered, even snarled, at federal power, but federal power was essential to the development of the West,” wrote Brands.

Lyndon Baines Johnson, 1963—1969

No president identified with his home state more than LBJ. “As a branding iron sears flesh, the memories of ... the Texas Hill Country etched themselves on Lyndon Johnson’s cortex,” wrote journalist Hugh Sidey. True to that legacy, no president was as renowned a horse trader. Though he’s often associated with bullwhip diplomacy, the “big daddy” of American politics’ real talent was for compromise. One of his favorite quotations came from Isaiah: “Come now, let us reason together.”

As president, Johnson negotiated through Congress his War on Poverty agenda as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. The effect of these landmark pieces of legislation tends to be focused on changes they brought to African Americans in the South. But their impact on the multiracial West — with its large communities of Native Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, African Americans, and other nonwhite populations — was similarly immense.

Though no president can claim an unblemished relationship with Native Americans, Johnson’s administration did more than most to work with tribes. (Historian Brands cites Ulysses Grant as another chief executive who attempted a more constructive approach to Native American relations.) His Office of Economic Opportunity created an internal “Indian Desk.” Sympathetic to the growing Red Power movement of the 1960s, he consistently promoted programs to bring economic aid to Native communities.

Johnson was restless — as a child he ran away from home on numerous occasions — like a man trapped in a world not big enough to contain him.

“He evoked memories of the frontier,” wrote historian John Milton Cooper. “Not six-shooter, cowboy days, as he tried to suggest with his Stetson hats and ranch, but the still earlier era of woods clearing, fantastic dreams and tall tales, the time of mythological creatures like Paul Bunyan and self-created characters like Davy Crockett.”

Sam Houston wasn’t a president of the United States, but he was twice elected president of the independent Republic of Texas, led the fight to wrest Texas from Mexico, and lived as full a frontier life as any American ever. Read about Houston’s incalculable impact on the West.

For more from the presidential package …

Theodore Roosevelt

Presidents and Native Peoples

Legislation That Made the West

Presidential Places

Photography: Images courtesy Joe Mamer Photography/Alamy Stock Photo, Library of Congress, White House Photo

From our July 2020 issue.