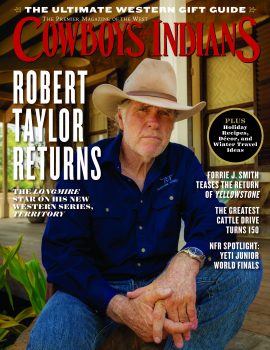

Painter Scott Burdick doesn't want you to look at his art. He wants you to read into the expressions of his subjects, and find the emotion from within.

Whether it’s an image of a Navajo woman standing with her arms crossed against a backdrop of Monument Valley or a young girl wearing long braids against a pink dress and a butterfly vest dressed for a powwow, painter Scott Burdick leaves his subjects’ faces expressionless, and even vague by design. “I like to have a neutral expression where people can read into it,” he says. He aims for realism, but only to a point. “I tend to paint people, both in the landscape, interiors, or even in a magical-realist environment. I’m telling a story, and I’m trying to create a visually interesting image or a person that you want to know more about.”

An open-ended storytelling quality of his images — mostly of people, and usually more women than men, he says — animates all of Burdick’s paintings. Even though the interpretation is his own, his objective is to spark an interest and to subtly create an emotional connection between image and viewer, so each person can impart their own stories onto the painting, instead of the other way around.

The emotion is there, but it’s subtle. You have to look for it; you must engage. And that’s precisely what Burdick is aiming for: the magic that happens when a story comes to life.

Weaver by Scott Burdick; oil on canvas; 24x18.

Weaver by Scott Burdick; oil on canvas; 24x18.

“Painting, writing, and filmmaking were what I was obsessed with as a kid,” Burdick, now 55, says from his studio outside of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains (his wife, painter Susan Lyon, has a separate studio on the property). “It’s all about storytelling and having something you want to say and convey to someone else. Some stories can only be told visually. What I like about painting is that it’s storytelling. It’s showing a visual image or something that I see in that person. I could tell you about it, but you won’t get it, because it’s not meant for words. I have to paint it.”

For Burdick, stories became the world he lived in when he was constantly and in and out of the hospital for operations on his club feet as a child. The oldest of four children, he lived with his family in a working-class neighborhood in Chicago. His mother accompanied him to his doctor visits and taught him to draw to pass the time. When he wasn’t reading books or writing stories, he was drawing in notepads, creating worlds and stories different from his own.

By the time he was in high school, he knew he wanted to be a writer or a painter. “I’d take the bus and the “L” on my crutches and go to take classes on Saturdays at the American Academy of Art; in the summer I would take life drawing classes,” he says. “I paid for them with money I made by working at a hot dog stand.” After that, he got a scholarship there and sealed his fate by perfecting his craft with nights and weekends at the infamous Palette and Chisel Club.

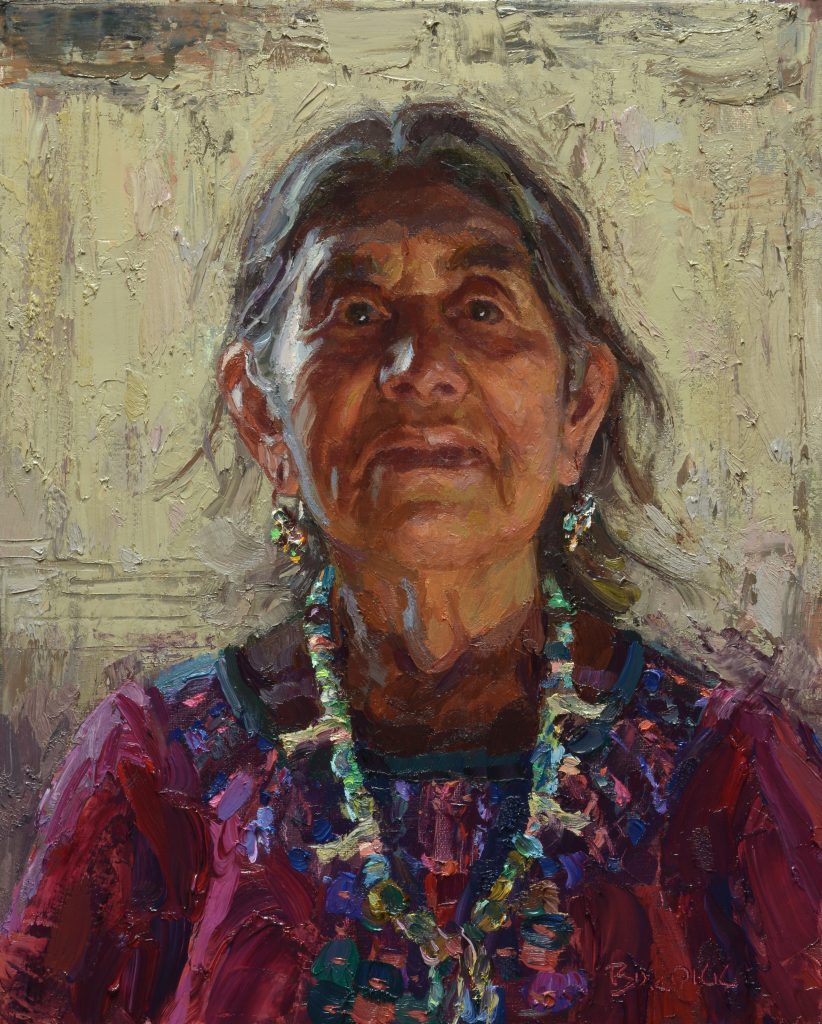

He hasn’t slowed down since. Today Burdick travels around the world for new subjects and stories, frequently packing up his oils, watercolors, and brushes and driving out West — Utah and Arizona, in particular. He paints what he finds there: landscapes, people, or both. “When I’m painting, I talk to the person the whole time, and I’m asking them about their story,” he says. “To me, that’s the most fun part. Sometimes I’m just talking to people and other times, I’ll tape their stories. The ones that are really interesting I’ll write up and put on Facebook or on Medium.” He might do as many as two to three paintings a day on these trips, reworking them in the studio or simply leaving them as they are.

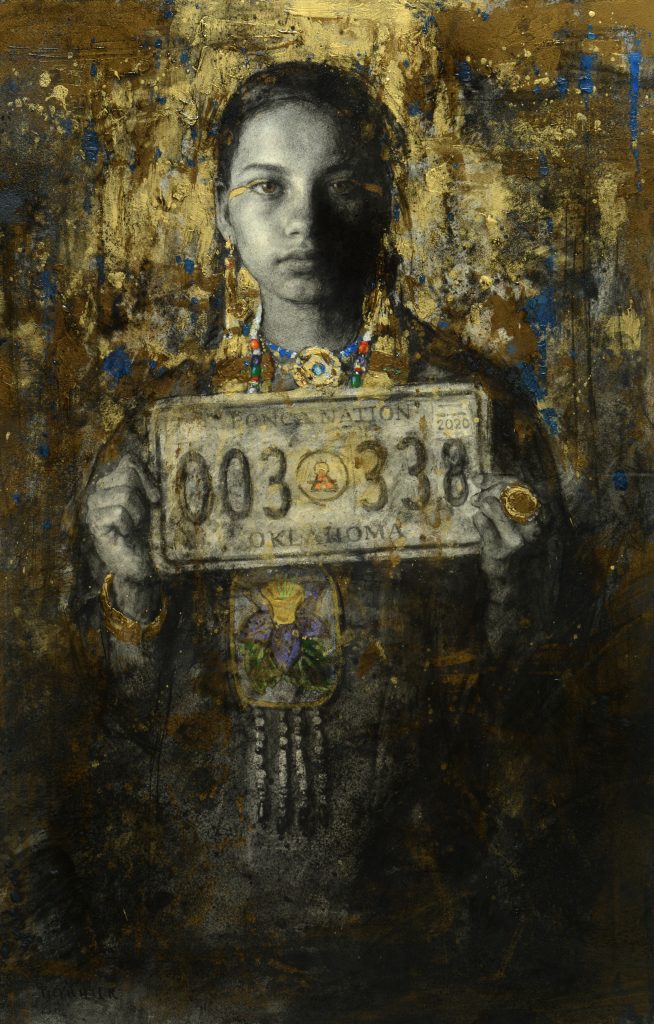

Of the many paintings he completes in a year, four of them will head, as they have for more than a decade, to the prestigious Prix de West exhibition in June at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. For last year’s show, when Burdick won the Robert Lougheed Memorial Award (voted on by the artists in the show for best group of paintings), he painted four portraits of women who live in the West, each representing a different racial group. “I titled the four paintings The Many, Colors, Of Our, and Nation,” he says, “Only one of the paintings would be a recognizably ‘Western’ painting, but the great thing about the Prix de West and the museum directors is that they take a broad view that includes the modern as well as the historical aspects of what the West is and what it might be in the future.”

As another for-instance, Burdick recalls the year he painted a couple of young Navajo children sitting in their minivan looking out the half-open window. “The kids were dressed thoroughly modern; the only hint of the West was some mountains in the background. I titled the painting Traditional Navajo Minivan. Susan Patterson, the museum’s exhibition curator, laughed in delight when she saw my odd submission and said that she was pretty certain she’d never seen a minivan in the show before.”

Although many of his paintings are of people and places in the West, Burdick doesn’t consider himself a “Western” painter. “I don’t put any kind of label on my paintings,” he says. “I love Western scenes, and I love Native culture. But I love all cultures. I don’t know what kind of painter I am. I’m just painting my experience, and some of that is in the West. Wherever I am, I always find something interesting.”

Ponca Nation by Scott Burdick; 36x24; charcoal and acrylic on paper.

Ponca Nation by Scott Burdick; 36x24; charcoal and acrylic on paper.

Visit Scott Burdick online at scottburdick.com. He’ll be exhibiting at Prix de West (art will be on view June 2 – August 7; the ticketed Art Sale Weekend takes place June 17 – 18) at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City (nationalcowboymuseum.org).

Photography: Courtesy of Scott Burdick.