Ride waves with surfers and horses with paniolos and discover the surprising links between aloha and howdy and a culture that’s as in tune with bridles as it is with boards.

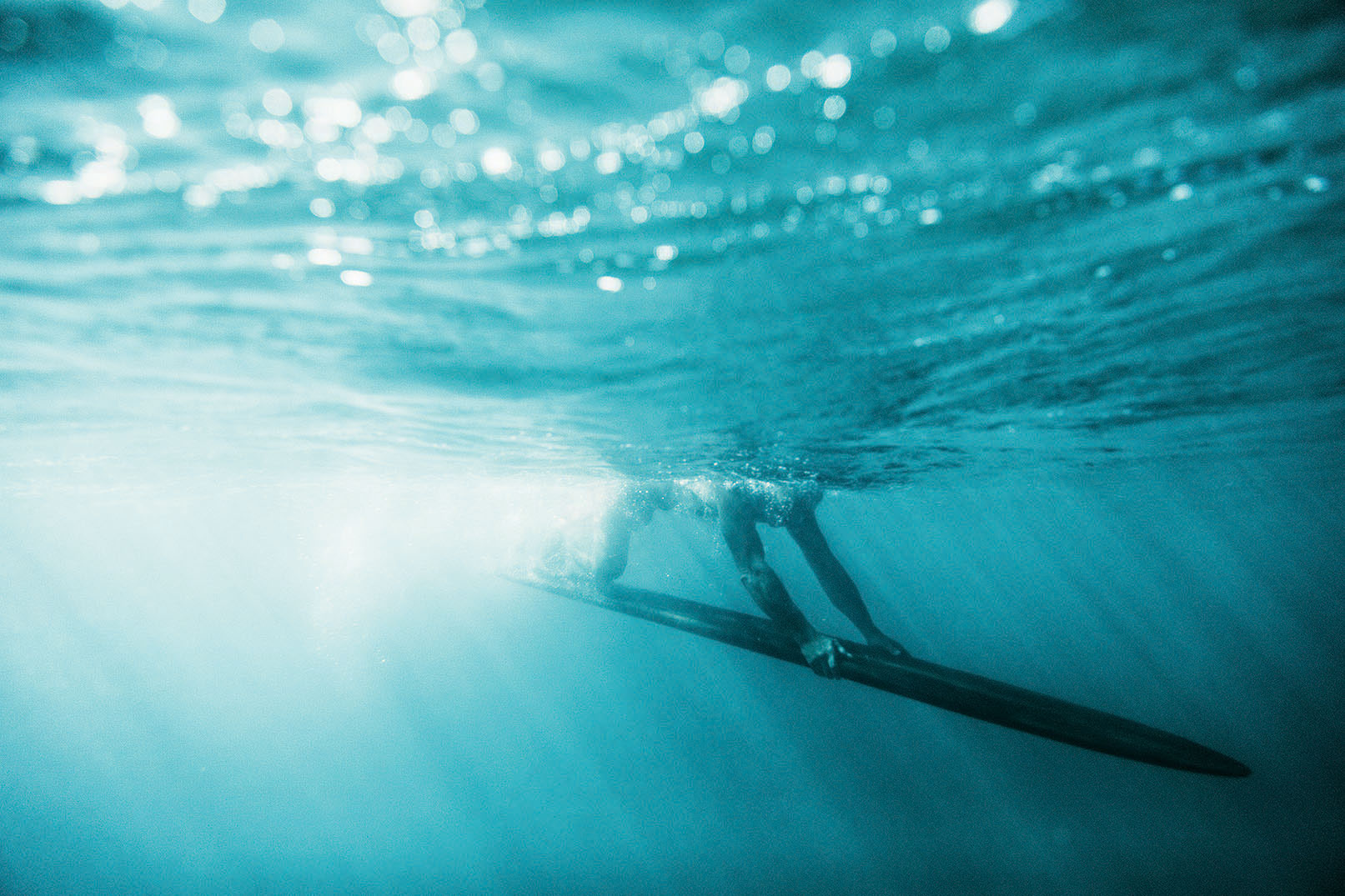

Here it comes, I thought. I’m going to crush this wave. My instructor, Micah Moniz, pushed my surfboard forward and told me to paddle. “Stand up!” he shouted as the wave reached the back of my board and lifted it gently up.

I pulled my feet forward, spun sideways, shuffled my hands to hold the board near my feet, let go … and faceplanted into the water just off of Waikiki Beach. That wave wasn’t bigger or faster than any of the dozen waves I had already successfully surfed in two days of lessons, and yet I suffered by far my worst crash. I cursed as I emerged from the Pacific Ocean, salt fresh on my lips. “You rushed it and looked down at your feet,” I told myself. “Don’t do that.”

I paddled back to Moniz, who was sitting astride his board, gently bobbing up and down with the waves. “You rushed it and looked down at your feet,” he said. “Don’t do that.”

Considering all of that happened in a fraction of a second, I was surprised Moniz captured the details. I probably shouldn’t have been. Moniz is a longtime instructor and former competitive surfer. The Moniz family has owned a surf school just off of Waikiki Beach for decades. Two of his brothers are professional surfers; his dad used to be. His sister, Kelia, is a two-time world champion and popular Instagram personality.

When people say surfing is in Hawaiians’ blood, the Moniz family is who they mean. Though they are among the most well-known families, any number of other families show similar devotion to the sport. Start there if you want to understand why Hawaiian surf culture is still thriving centuries after it started.

The waves rolled gently into a tiny bay tucked onto Oahu’s North Shore at Turtle Bay Resort. I sat astride a quarter horse named Cali and peered at a boat hundreds of yards offshore. To the left of the boat, white spray shot out of the ocean, the result of whales surfacing for air.

My guide, Vera Lee, resumed our tour. We turned inland, and our horses walked through a well-worn section of trail known as Candy Land because it cuts through a field of sweetgrass. Cali buried his face in the green delicacies like my kids bury their faces in their Halloween baskets.

I pulled on the reins, hoping to get him to stop munching and continue walking. I gave up after a few half-hearted attempts because if I were walking through a field of hummus and crackers and someone tried to pull me away from it, I wouldn’t yield either.

From a horse’s point of view, Hawaii is delicious. More than that, given the state’s perfect weather, abundance of edible plant life, and spectacular views, Hawaii is an ideal place for horses and the riders who love them.

Start there if you want to understand why Hawaiian cowboy culture — or paniolo culture as it’s known in Hawaiian — is thriving 217 years after horses arrived on the islands.

Surf and saddle. Saddle and surf. With help from the state’s tourism department, I visited Hawaii to explore these two cultural institutions that have played such a crucial role in the history of the Aloha islands. Surfing’s place in Hawaiian culture and history is well known. Hawaii’s cowboy history and culture are not talked about nearly as much, but they played, and still play, a foundational role in shaping the state.

Before there were cowboys in Hawaii, there were cows. Lots and lots and lots of cows. In 1793 British Navy Capt. George Vancouver gave King Kamehameha six cows and a bull as gifts. Kamehameha placed a kapu over them, a sacred order banning their killing.

The cows devoured the Hawaiian countryside like Cali devoured the sweetgrass. They were the only large mammal in Hawaii and had no natural enemies. They ate and propagated and ate and propagated … until the islands were overrun.

King Kamehameha III lifted the kapu. That left open the question of how to manage the cows. Private property ownership didn’t exist yet in Hawaii, so what passed for cattle management policies were closer to hunting than wrangling.

Horses arrived in 1803. They were used to collect the cows, one by one, often at the top of mountains. Workers skinned the cows, removed their meat, salted them up there, and hauled them down, one by one. At that rate, it would take forever, because by the mid-1800s, cows numbered 25,000. A better solution was needed.

Hawaiian cowboys didn’t become cowboys — cowboys of the western United States — until after 1832, when King Kamehameha III visited California and was a guest at a large ranch. His hosts took him to what was essentially a branding, and he was amazed by what he saw. He invited a dozen or so vaqueros, or Mexican cowboys, to come to Hawaii to teach Hawaiians how to wrangle.

The transition happened quickly. Parker Ranch, one of the biggest in the country and still in operation today, was established in 1847. Eventually paniolos who once harvested one cow at a time could take dozens in one day. And after the Great Mahele land redistribution of 1848, which made private land ownership possible, cowboy culture became permanently entrenched in Hawaii.

The known origins of surfing are a little hard to pinpoint in terms of who did what and when and where. It’s widely believed that surfing started in Hawaii. Michael Wilson, who designed Mai Kinohi Mai: Surfing in Hawaii, an exhibit tracing the history of surfing (mai kinohi mai means “from the beginning”), at Honolulu’s Bishop Museum, says ancient stories detail the volcano goddess Pele’s passion for surfing. The oldest known surfing relic is a board used by a chief named Keopulepule in the late 1700s. Because significant boards are often handed down across generations, the board might date back even further than that.

Surfing culture certainly does. It was well-developed before contact with European civilization. “When Capt. Cook came [in 1778], it was so deeply embedded in the culture, it was as important — or as much a part of the culture — as growing food and religious ceremonies,” Wilson says. “It was built in.”

The surfers and cowboys who emerged from those incongruous histories nevertheless share much in common. After taking lessons in both surfing and horseback riding in Hawaii, I was struck by similarities in how surfers and cowboys carry themselves.

They have the confidence to constantly put themselves in danger while holding deep respect for that danger. A wave can snap you in half, or a horse can stomp your guts, at any moment. Facing those fears has not made them cocky. It has made them humble, because they know the second they get cocky is the second a wave snaps them in half or a horse stomps their guts.

One of the highest compliments you can give a surfer in Hawaii is to call him or her a waterman or waterwoman. “A waterman or woman is somebody who is comfortable in the ocean, connected to the ocean,” Wilson says. “They understand the ocean from several perspectives, understand its connection to the culture. There’s a communing with it.”

Similar reverence is attached to being called a cowboy. “Cowboys in Hawaii never call themselves paniolo,” says Dr. Billy Bergin, a historian at Paniolo Heritage Center at Pukalani Stables in Waimea. Bergin grew up working on Hawaiian ranches and was a veterinarian at Waimea’s Parker Ranch for more than two decades. “We’ve romanticized that word. It has a nice ring to it. But if you went to a branding, they would say, ‘I’m a cowboy.’ You know why? The term cowboy is honorable. All across America, it connotes straightness, trueness, honor.”

After my surfing lesson with Moniz, I visited the Bishop Museum, where Tom “Pohaku” Stone worked on a surfboard, as he does every Thursday. He makes them from wood, sculpting and crafting them with care you don’t find in a board made out of fiberglass from a mold. Stone’s boards are as much art as they are sporting equipment.

A few days later, I visited Bergin at Paniolo Heritage Center. He told me that when the vaqueros brought cowboy culture to Hawaii, one reason native Hawaiians adapted so well was that they already had the skills necessary to perform the tasks. They just needed to use them in a new way.

They knew, for instance, how to carve and weave and simply transferred those skills to saddle making. As Bergin walked through the heritage center, he fingered the braiding of a 70-year-old saddle. “This is almost artistic, it’s done so well,” he said.

Surfers and cowboys share an unshakeable belief that they have a responsibility to care for the natural resources from which they take so much joy. This is baked into their lives, a worldview, a foundational part of how they live. I saw this in surfers’ care for the whole of the ocean, not just the waves they ride or the beaches they walk on to get to them. I saw it again after a ride on a quarter horse named Raider at Gunstock Ranch on Oahu.

Gunstock Ranch covers 900 acres, all of them green and lush. My 90-minute ride featured spectacular views of the ocean to the east and Ko’olau Mountains to the west. A few years ago, the ranch conducted a survey of the plant life on 80 of its acres. Only two plants were native to Hawaii. Not two types of plants — two plants, period. To return the land to how it once was, Gunstock dedicated 500 acres to bringing back long-lost plant life.

The ranch has planted more than 15,000 monarch milo trees in just more than two years.

After my ride, I got on my hands and knees and added one more.

“It’s critical that we take care of what we have, take care of our island, take care of our earth,” said my guide, McKenzie Mitchell.

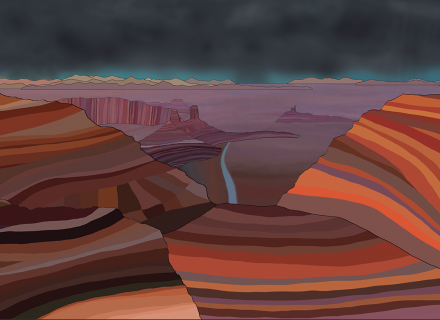

I checked out of the Kamuela Inn in Waimea and drove to Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. The trip through the center of the island of Hawaii reminded me of drives I’ve taken across the West. I saw more cows and horses than people. Endless acres of ranchland lined the highway. Familiar wire fences demarcated property lines, and arched signs with clever ranch titles stood at entryways.

Granted, the view wasn’t exactly the same as on the mainland. Hawaii is lusher and greener than, say, Texas. Nor have I ever gazed into the distance and seen surfers riding waves in and paddling back out in, say, Utah. And I know of no Wyoming ranches that abut lava fields.

I surfed and rode horses for a couple of days each, but I left Hawaii no closer to being a surfer or a paniolo than I was before I got there. There remained an unbridgeable distance between trying the sports and living for them — the difference between doing and being.

As we floated between waves, Micah Moniz said he could discern the difference between poseur surfers and true surfers by how they carried their boards. In the same way, a cowboy can spot a well-trained horse by how it stands — and a true horseman by the way he sits a horse. They simply know these things. They have lived the experience so much they have crossed over from doing to being.

Which brings me to the great legends, true and not, of Hawaiian surfing and cowboy history. The deep reverence for stories might be the strongest bond the two sports share — stories that tend to reveal a shared sense of living authentically in the moment.

When Bergin is going to weave a particularly good tale, he prefaces it with “and this is how it went.” That’s how he began the story about Ikua Purdy.

And this is how it went: In 1908, Purdy and two cousins traveled from Hawaii to Cheyenne, Wyoming, to participate in Cheyenne Frontier Days, then and now one of the world’s most prestigious rodeo competitions.

Purdy and his cousins arrived in Cheyenne as exotic curiosities, wearing colorful leis and vaquero chaps. But Purdy shocked the rodeo world by winning the steer-roping competition. As if the story wasn’t good enough already, a legend sprung up around it. The Cheyenne cowboys had given him a crummy horse, the story goes, so crummy that Purdy took him to a riverbed to break him in. That legend had the air of truth: Any paniolo knows a riverbed would be a good place to take an unruly horse, because the soft riverbed would make it impossible for the horse to buck.

Bergin didn’t believe the legend. First of all, it flew in the face of cowboy culture. A real cowboy would have let Purdy ride his best horse, not his worst. There’s no honor in beating a cowboy when he’s on a bad horse. And Bergin had seen a picture of Purdy with the allegedly bad horse. Just as Moniz knows a good surfer by sight, it’s the same for Bergin and horses. Purdy’s horse had a strong, trained, regal bearing.

Bergin flew with a contingent of Hawaiians to Cheyenne for the 100th anniversary of Purdy’s historic win. The very fact they visited Cheyenne suggests the legend of the bad horse couldn’t be true. Cheyenne would not welcome Hawaiians to celebrate the anniversary if they had tried to fix that rodeo.

When Bergin arrived in Cheyenne, he wanted to see where the legend was born, even if it wasn’t true, maybe get to the bottom of what he suspected was a tall tale.

He asked the mayor to show him the riverbed where the alleged horse-breaking took place.

Cheyenne, the mayor said, has never had a river.

The best ending of that transpacific tale, though, wouldn’t be written till later. Ikua Purdy had already been inducted into the National Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1999 for his famous win in 1908. But the lei honoring him that his grandson had brought to Cheyenne in 2018 was falling apart where it hung next to Purdy’s portrait in the CFD Old West Museum. That’s when Mike Kassel, the assistant director of the museum, figured out a most fitting final flourish. In June 2020, he got down in the arena dirt and conducted a lei burial — one of several ways to dispose of a lei in honor of someone — near the very site where Purdy, the first non-Wyomingite to win the competition, put Hawaii’s cowboys on the map of the West.

From our April 2022 issue

For more about travel in the Hawaiian Islands, visit gohawaii.com.

Photography: Johnson/Courtesy Hawaii Tourism Authority; Heather Goodman/Courtesy Hawaii Toursim Authority