You know him for his celebrated majestic landscapes of the American Frontier. Now a new exhibit looks at his legacy as a painter of history.

Born in Germany in January 1830, Albert Bierstadt came to the United States with his parents as a 2-year-old. Living in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he would grow up to become one of the foremost painters of the American West.

He studied painting in Europe and developed a style distinct from that of both New York’s Hudson River School and Thomas Moran’s English aesthetic, and his name became synonymous with luminous sweeping vistas of Western landscapes.

Bierstadt’s paradisiacal renderings of Yosemite Valley generated tremendous publicity. His Edenic vision of an untouched West struck a chord with a country riven by the Civil War and could have ultimately been influential in President Abraham Lincoln’s 1864 signing of the Yosemite Grant Act, which established Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove as protected wilderness areas.

This is the Bierstadt with whom we are familiar. But there is much more to him. Now, the major exhibition Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West attests to just that. Conceived by Peter H. Hassrick, Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, it offers a fresh, complementary view of the painter’s career, concerns, and complexities.

We talked with Hassrick’s co-curators — Karen McWhorter, Scarlett Curator of Western American Art at the Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, and Laura Fry, Senior Curator and Curator of Art at the Gilcrease Museum — about the groundbreaking exhibition that shows the iconic artist in a new light.

Cowboys & Indians: This exhibition presents a Bierstadt beyond his well-known reputation for epic romantic landscapes and delves into his empathy for the American Indian and bison. What were his attitudes about wildlife conservation and Native sovereignty?

Karen McWhorter: To date, Bierstadt’s landscape paintings have been critically assessed to a greater extent than any other aspect of the artist’s oeuvre, so much so that the painter is rarely appreciated for the broader range of subjects he developed beyond Western scenes. Besides being a skilled and successful landscapist, Bierstadt was also a renowned history painter, but as yet, Bierstadt’s figural narratives of the American West have less frequently received the attention of scholars. These are the focus of our exhibition.

Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West reexamines Bierstadt through a new lens trained on the artist’s history paintings featuring Plains Indians and the American bison. With new perspectives on Bierstadt as a principal chronicler of a changing West, this exhibition explores the ways in which the artist approached bison and American Indians as prime subjects for his art. It also critically reconsiders the artist’s engagement with not just the aesthetic issues of his time but also contemporary political and social debates around wildlife conservation and management in America, our national parks, and the destiny of indigenous peoples of the American West.

Bierstadt’s interest in wildlife conservation and management is evident in his actions, his affiliations, and his art. He was a passionate outdoorsman and skilled hunter, but from his first trip West and throughout his life, he was often more interested in painting animals than he was in hunting them. In 1863, he accompanied a bison hunt in Kansas, but chose to sketch the beasts felled by his compatriots rather than participate in the action. Throughout the 1870s, he continued to paint Western wildlife.

In 1888, Bierstadt was made a charter member of the Boone and Crockett Club, [North America’s] first conservation group committed to preserving and managing wildlands and wildlife. The club’s founding mission centered on protecting Yellowstone National Park’s animal populations from poachers. Irresponsible hunting had nearly decimated the remnant herd of American bison and other big game residing in the park.

For his part, Bierstadt called attention to the plight of bison in the West by wielding the tools of his trade — paintbrush and canvas. The same year he joined the Boone and Crockett Club, he began work on two major paintings, both titled The Last of the Buffalo. These canvases glorified historical subjects, but spoke to contemporary concerns. They depict an earlier chapter in the American West when bison ranged in innumerable herds and the region’s indigenous peoples had not yet faced the new and incredible hardships wrought by newcomers to the West and the American government.

C&I: What was his relationship with our national parks?

McWhorter: Thomas Moran is often recognized as Yellowstone’s most influential early painter. It was Moran’s colorful depictions of the region which helped convince Congress to set aside Yellowstone as the world’s first national park and which helped introduce the public to the area’s natural wonders. Albert Bierstadt had been invited to join the 1871 expedition to Yellowstone, but declined the opportunity in order to fulfill a major obligation to a California patron. He took his first trip to Yellowstone a decade later, in 1881. Though he was not among the first artists to depict the area, he became an important champion of the park.

Bierstadt traveled to Yosemite in 1863, the year before the area officially became a public park. Though he was only indirectly involved in persuading Congress to protect Yosemite, Bierstadt’s paintings recorded and celebrated the area’s grandeur, picturing the landscape and its wildlife as worthy of preservation.

Several of Bierstadt’s impressive paintings of the areas which would become Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Rocky Mountain national parks are included in the exhibition.

C&I: And his relationship with indigenous peoples?

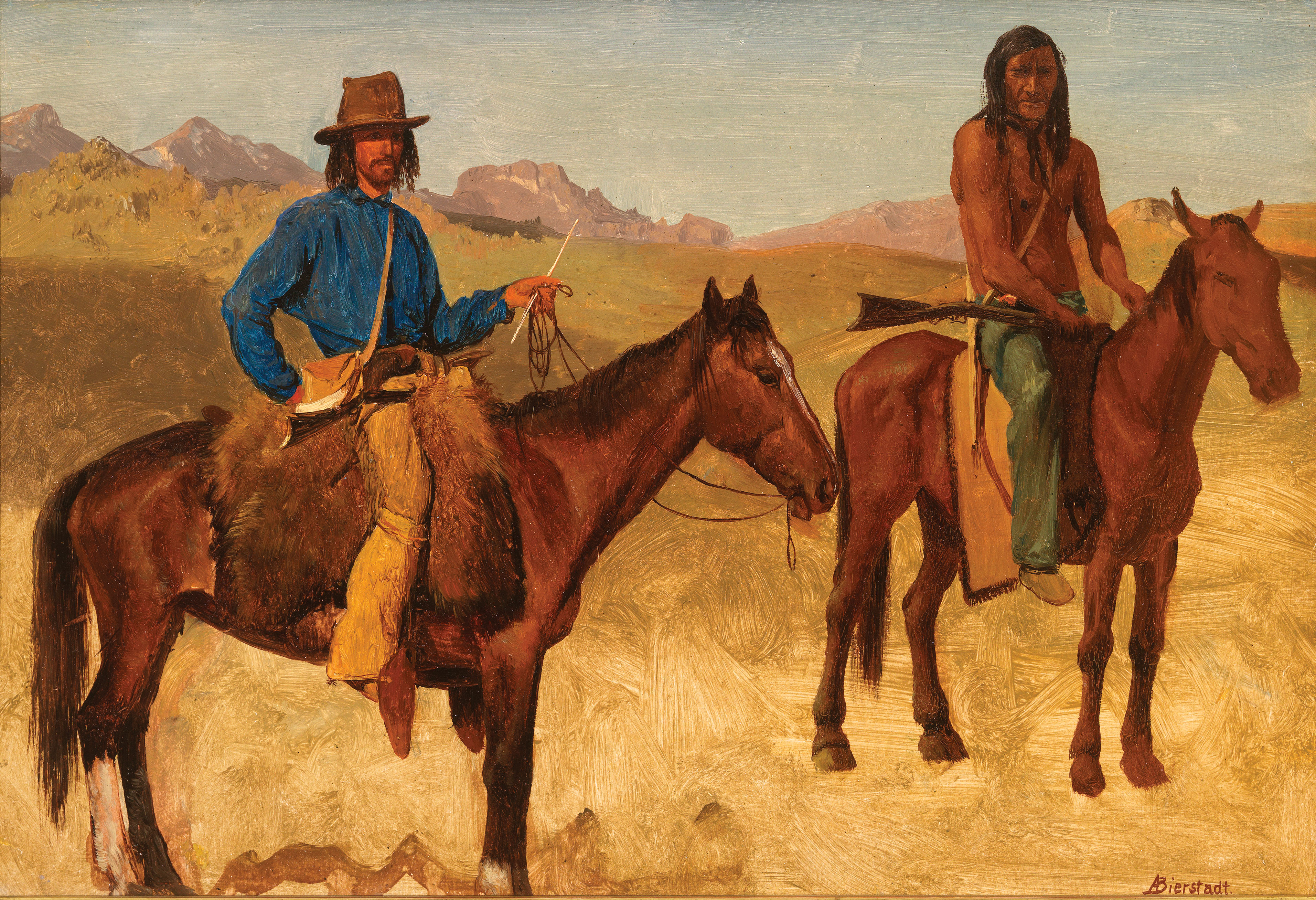

McWhorter: From his first trip West, Bierstadt showed great interest in the region’s Native cultures. His written accounts of the 1859 expedition, oil studies, and stereographs he made along the Oregon Trail — many picturing Native Americans and their camps — all attest to this early admiration. Bierstadt is known to have met with and sketched Pawnee, Sioux, Shoshone, and Kansa Indians on this westward journey and gave special prominence to these peoples in studio paintings he created back East. He also appreciated traditional Native arts and amassed a collection of Indian artifacts.

Bierstadt’s double portrait of the Shoshone Chief Washakie and Col. Frederick W. Lander positions the two men on even ground, presenting them as prominent leaders who share an interest in establishing amicable relations between their cultures. In paintings like this one — included in the exhibition — Bierstadt’s high esteem for Native peoples is on display.

Like many other European and American artists working in the West in the 19th century, Bierstadt professed concern for the fate of the region’s indigenous peoples. And yet some of his paintings also helped promote the West as a site of opportunity for European and American emigrants. The relationship between Bierstadt’s apparent empathy for American Indians and his creation of paintings which seem to promote Manifest Destiny is a complicated one, but so, then, was Bierstadt a complicated man, as were his patrons.

C&I: Clearly not just a painter of pretty pictures.

McWhorter: This exhibition and its accompanying catalog explore contemporary events and issues, and new perspectives on the artist’s biography and his work to reveal the complexity of Bierstadt’s persona and artistic vision. Bierstadt was undoubtedly influenced by the commonly held beliefs of his milieu, but against this backdrop, he developed his own particularly personal perspectives on the West and its inhabitants, which, in turn, informed his paintings. Though his motivations may have ranged from moral obligation to entrepreneurial zeal and his subjects swayed by the demands of his patrons, Bierstadt was an astute and sensitive recorder of the West and its inhabitants during his time.

C&I: The show also presents a rarely emphasized aspect of his legacy: Bierstadt as a history painter. What’s a good example of one of his history paintings and what it was meant to convey?

McWhorter: The centerpiece of the exhibition is one of Bierstadt’s last great paintings, one of two almost-identical and colossal canvases titled The Last of the Buffalo. When Bierstadt crafted these works in 1888, the harrowing repercussions of westward expansion by Euro-Americans were everywhere resounding. By the last decades of the 19th century, Native people had been pushed onto reservations, their lives and cultures forever altered. The American bison, which once roamed the West in great herds, faced near extermination, the dwindling population conscribed to newly established Yellowstone National Park and a few private herds. Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo paintings were his odes to an earlier era and gave voice to contemporary concerns about the fates of Native peoples and wildlife in the West.

According to Peter Hassrick, “In their symbolic grandeur, the companion works elevated the Indian and the buffalo to equal, mythic status. An equestrian Native hunter and a powerful bison bull battle for survival in an ascendant flash that privileges neither as a winner but presents both as claimants of the viewers’ consciousness. The shared angst of the protagonists compels us to respond to the poignant drama by considering that the potential loss of either is deeply tragic and that Anglo America has facilitated this ironic scenario where out of bounteous plenty has come profound loss.”

C&I: What, for you, are the standout works in the show?

McWhorter: This exhibition gathers over 70 works of art from more than 30 private collections and institutions nationwide, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

The centerpiece of the exhibition will be Bierstadt’s The Last of the Buffalo (1888) from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s collection.

Another standout work will be the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s The Buffalo Trail (1867). This painting, a luminous canvas measuring 32 inches tall by 48 inches wide, depicts a group of bison crossing a river. The prairie stretches endlessly behind the animals, dissolving into the sun’s golden glow. The bison march through placid waters toward a verdant scene of sheltering trees and thick green grass. A sense of fecundity and calm pervades. This is Bierstadt’s depiction of the halcyon days of the American bison in the West. The animals are shown here in great numbers, with plentiful resources to support their populations. The threats of hunters and railway lines are nowhere to be seen.

Bierstadt created other paintings which carry the bison’s story from its zenith to the species’ near-extermination, many of which will be shown in the exhibition. As a kind of first chapter to a cautionary tale, The Buffalo Trail symbolically underscores these iconic animals’ historical abundance in the West and celebrates their central importance to the region’s ecology and our national identity.

Another work which will resonate with our audience is the Museum of the South Dakota State Historical Society’s nearly 9-foot-wide painted muslin (ca. 1900 – 1920) created by Lakota Sioux artist Standing Bear and interpreted in the exhibition by contemporary artist and scholar (and Standing Bear’s great-grandson) Arthur Amiotte. This special loan underscores the historical importance of bison to Plains Indian peoples.

Not to be missed is a monumental triptych by William Jacob Hays — three paintings, created between 1861 and 1863, which have not been exhibited together in modern times. Hung side by side, they form a nearly 18-foot-wide saga of the American bison, from the species’ heyday to its destruction on the Plains. Paintings like these by Bierstadt’s contemporaries and predecessors are included in the exhibition to illuminate artists’ roles in debates around the conservation of land and wildlife in the 19th century.

C&I: Bierstadt was one of many artists to join expeditions and paint the majestic scenes out west. Why is he so important?

Laura Fry: Today, scholars and art historians regard Bierstadt as one of several leading 19th-century American artists whose work helped shape public perceptions of the American West. Following his first journey through the American West in 1859, Bierstadt began a series of “great pictures,” large-scale paintings depicting the dramatic landscapes of the Rockies and Sierra Nevada mountains. While he received decidedly mixed reviews from art critics, Bierstadt’s work remained enormously popular with the American public in the mid-19th century.

In 1864, when he first displayed the 10-foot-wide painting The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak, crowds lined up to see it. Bierstadt sold the painting for the astonishing sum of $25,000, one of the highest prices yet paid for an American artwork. Bierstadt’s work was widely distributed in the 19th century, a result of his entrepreneurial zeal. His paintings traveled the world, and many of his works were reproduced as prints. As a result, his majestic images of the American West influenced public perceptions of these landscapes.

C&I: What impact did Bierstadt’s luminous landscapes have in his era?

Fry: In the 1860s, Bierstadt was one of the first artists to introduce the vast scale of the Western landscape to the public. While some critics (who had never traveled to the West) regarded his lofty mountains as exaggerations, others believed he captured the true nature of the Western landscape. Near the end of Bierstadt’s career, when his work had largely fallen from favor, one critic noted, “It was he who revealed in every picture, in large perspective views, some of the thousand beauties that our country contains.”

Westerners themselves greatly appreciated his paintings. When reporting Bierstadt’s passing in 1902, one Montana newspaper wrote, “His pictures did more than anything else to give the outer world an adequate idea of the scenic glories of the Yellowstone and of the Rocky Mountains. ... Bierstadt is dead, but his works will live for ages.” And so they have. Today, Bierstadt’s works continue to elicit a variety of responses. In 21st-century exhibitions, doctoral dissertations, and publications, he is continually recognized as a leading 19th-century American artist.

C&I: What are the lasting impact of his work and his place in the “canon”?

Fry: The art historical canon is a strange construct — and often “the canon” reinforces existing power structures and restricts new interpretations of the past. Bierstadt’s work does not rely on the canon for its impact.

For many years in the early 1900s, critics roundly mocked Bierstadt’s paintings and the work of his Hudson River School peers. But the depth and variety of Bierstadt’s oeuvre did not remain swept under a rug. By the mid-20th century, his works attracted attention and new critical reception on multiple fronts. In 1949, Thomas Gilcrease proudly included Bierstadt’s work in his new Gilcrease Museum, the first major museum dedicated to Western American art. Since then, Bierstadt has been consistently recognized as one of the leading 19th-century artists of the American West, and as an artist who shaped views of the entire Rocky Mountain region.

But other aspects of his work have also risen to fame. In 1963, the Florence Lewison Gallery in New York organized the first-ever solo exhibition of Bierstadt’s work. Rather than focusing on Bierstadt’s mighty landscapes, the Lewison Gallery showed his plein-air oil sketches and compared their simplified compositions to contemporary abstract art. Since then, Bierstadt’s small sketches have been praised for their “absolute modernity,” and his sketches have been compared to work by James McNeill Whistler and even Mark Rothko.

With this new exhibition, by focusing on Bierstadt’s connection to the early conservation movement in the United States, we hope to bring another dimension to Bierstadt’s work forward and demonstrate the wide-ranging impact of his artistic career.

C&I: What else do you hope visitors will take away from this show?

Fry: By exploring an underappreciated side of Bierstadt’s career, we hope to create a nuanced view of his work. Like all people past and present, Albert Bierstadt was a complex human being, an individual who was both a product of his time and seeking to enact change.

In a large sense, I hope this exhibition will prompt visitors to consider how art impacts the world around us. In Bierstadt’s case, his paintings helped drive the movement to save the entire species of American bison from extinction. The tensions and issues we face as a society today have long-established roots, going back to Bierstadt’s own time. The themes in this exhibition can provide part of the historical context for today’s concerns about land preservation, resource extraction, and Native American sovereignty. By exploring Bierstadt and his impact, we hope visitors will gain a greater appreciation for the nuance and complexity of our world today.

Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West is on view June 8 – September 30 at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming; and November 3, 2018 – February 10, 2019, at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

From the June/July 2018 Issue.

More Art Gallery

David Jonason

Z.Z. Wei: Shadow Stories

10,000 Years of Walking the West