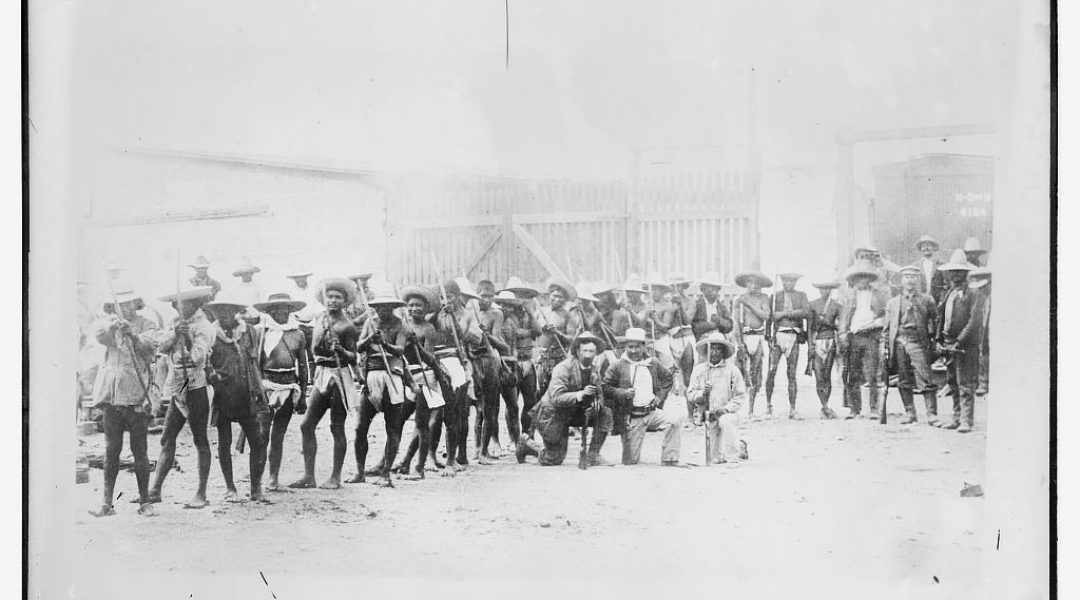

The final battle between Native American fighters and U.S. Army forces occurred 100 years ago in Bear Valley near the Arizona border with Mexico.

For the most part, armed American Indian resistance to the U.S. government ended at the Wounded Knee Massacre December 29, 1890, and in the subsequent Drexel Mission Fight the next day. But the last battle between Native Americans and U.S. Army forces — and the last fight documented in Anton Treuer’s (Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe) The Indian Wars: Battles, Bloodshed, and the Fight for Freedom on the American Frontier (National Geographic, 2017) — would not occur until 26 years later on January 9, 1918, when a group of Yaquis opened fire on a group of 10th Cavalry soldiers in a tragic case of mistaken identity.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, the Yaqui people were fighting the government of Mexico, hoping to establish an independent homeland in Sonora. Yaqui warriors joined in the rebellion when the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, but by 1916 Mexican generals were claiming Yaqui land as their own, which led to renewed conflict between Yaqui and Mexican military forces.

During this period Yaquis would cross the border for farm work in Arizona, where they would use their wages to buy firearms and ammunition and then return to Mexico to keep up the fight. As for the U.S. military, of course, its forces were mostly in or on their way to Europe for the Great War. But cavalry forces, seen as obsolete against machine-gun fire, were left behind to guard the border and against the unlikely event of an Indian uprising.

In late 1917, Sonora military governor Gen. Plutarco Elías Calles asked the U.S. government to help stop the arms smugglers bringing weapons into Mexico. Meanwhile, local ranchers were complaining about bands of Yaqui trespassing and occasionally slaughtering their cattle for food and sandal leather.

The Nogales, Arizona, subdistrict commander, Col. J.C. Friers, issued orders for increased patrolling in the area, and forces from the 35th Infantry Regiment and the 10th Cavalry Regiment spread out to protect towns along the border. Among them were Capt. Frederick H.L. “Blondy” Ryder and his Troop E.

On January 8, cattleman and Ruby Mercantile owner Philip C. Clarke rode into camp to report that a neighbor found a freshly killed cow, with only parts of its hide stripped for sandals, in the mountains to the north. The carcass suggested the Yaqui must be nearby.

Capt. Ryder sent 1st. Lt. William Scott and other men to watch the trails, and about midday the following day, Scott signaled that the Yaqui were in sight and on the move. Troopers rode out to the location, dismounted, and advanced in a skirmish line through a draw but didn’t see the Indians. Heading back to the horses using a different route, Ryder stumbled upon a cache of discarded packs. The Yaqui were in the immediate vicinity and knew they were being pursued. The U.S. troops continued up the canyon until suddenly the Yaquis fired on them.

A 10th Cavalry historian, Col. Harold B. Wharfield, interviewed fighters from both sides of the fight and wrote the following:

“[T]he fighting developed into an old kind of Indian engagement with both sides using all the natural cover of boulders and brush to full advantage. The Yaquis kept falling back, dodging from boulder to boulder and firing rapidly. They offered only a fleeting target, seemingly just a disappearing shadow. The officer saw one of them running for another cover, then stumble and thereby expose himself. A corporal alongside of the captain had a good chance for an open shot. At the report of the Springfield, a flash of fire enveloped the Indian’s body for an instant, but he kept on to the rock.”

The troopers finally overtook a group of 10, who were covering for the escape of the rest of the band into Mexico, and took them captive. Ryder later wrote of the engagement that it “was a courageous stand by a brave group of Indians; and the Cavalrymen treated them with the respect due to fighting men. Especially astonishing was the discovery that one of the Yaquis was an eleven-year old boy. The youngster had fought bravely alongside his elders, firing a rifle that was almost as long as he was tall.”

One of the prisoners, the chief of the group, had been grievously wounded. “This was the man who had been hit by my corporal’s shot,” Ryder wrote. “He was wearing two belts of ammunition around his waist and more over each shoulder. The bullet had hit one of the cartridges in his belt, causing it to be exploded, making the flash of fire I saw. Then the bullet entered one side and came out the other, laying his stomach open.”

It turned out the Yaqui had mistaken the Buffalo Soldiers for Mexican troops. The captives, including the wounded chief, were escorted to Nogales and stoically endured a miserable 20-mile ride on horses despite their lack of riding experience, arriving blistered and bloodily chafed. The chief died in the hospital the next day.

The surviving prisoners were held at Arivaca while the Army awaited orders from Washington and adapted so well to military life that they all, including the 11-year-old, volunteered to enlist. Eventually they were sent, in chains, to Tucson for trial in federal court, where they were charged with illegal exporting of arms without a license. The adults were sentenced to 30 days, a much preferable outcome than deportation to Mexico, where they would have been executed.

Photography: Library of Congress

Read more about the Indians Wars in the January 2018 issue.