Within their rugged freedom and haunting beauty, the badlands of North Dakota hold a key to healing and transformation.

Before he was the strapping outdoorsman of history books and lore, Teddy Roosevelt was a scrawny, asthmatic city slicker. A trip to the badlands of North Dakota, where he got hooked on the cowboy life, changed all that. “It is certainly a most healthy life. How a man does sleep, and how he enjoys the coarse fare!” Roosevelt exclaimed. You have only to be horseback in this exquisitely forbidding country to understand how the place that made a president gets a hold of the soul and won’t let go.

Some call it The Land God Forgot. Its harsh terrain and surreal rock formations might seem to bear that out. But after nearly 25 years of riding in the North Dakota badlands and the national park named in honor of Roosevelt, I’m more inclined to call it God’s Country. I originally came for its excellent horseback riding, but over the years I’ve found something deeper. In the saddle amid the fantastic solitude and virtuosic landscape, there is renewal and comfort — and a certain steeling of the spirit and undeniable self-discovery.

There came a day when I desperately needed the strengthening power of this place. Roosevelt needed it, too. He sought solace and escape in the badlands’ beautiful desolation in 1884 after losing both his wife and mother just hours apart on the same bitter February day. For me, the trial was cancer. In 1991, as chemo ran through my veins, I traveled here in my mind. I visualized myself on a cliff overlooking the striped sandstone formations and felt the healing powers of the land envelop me. That fall, postponing my last treatment, I made the trip I had visualized during chemo, venturing once again to that ancient place formed by volcanic ash and abrasive silt to ride and heal.

On that journey, a young Spanish Mustang named Al carefully bore my fragile body over rugged trails. My faithful steed for 19 years, Al also loved the badlands, and he carried me through scrub and sandstone to spiritual renewal and health. Al’s gone now, but I’m still here. As a Stage IV cancer survivor, I return every fall to our sacred place to give thanks to the land and the horse that helped save my life.

“I never would have been President if it had not been for my experiences in North Dakota.” — Theodore Roosevelt

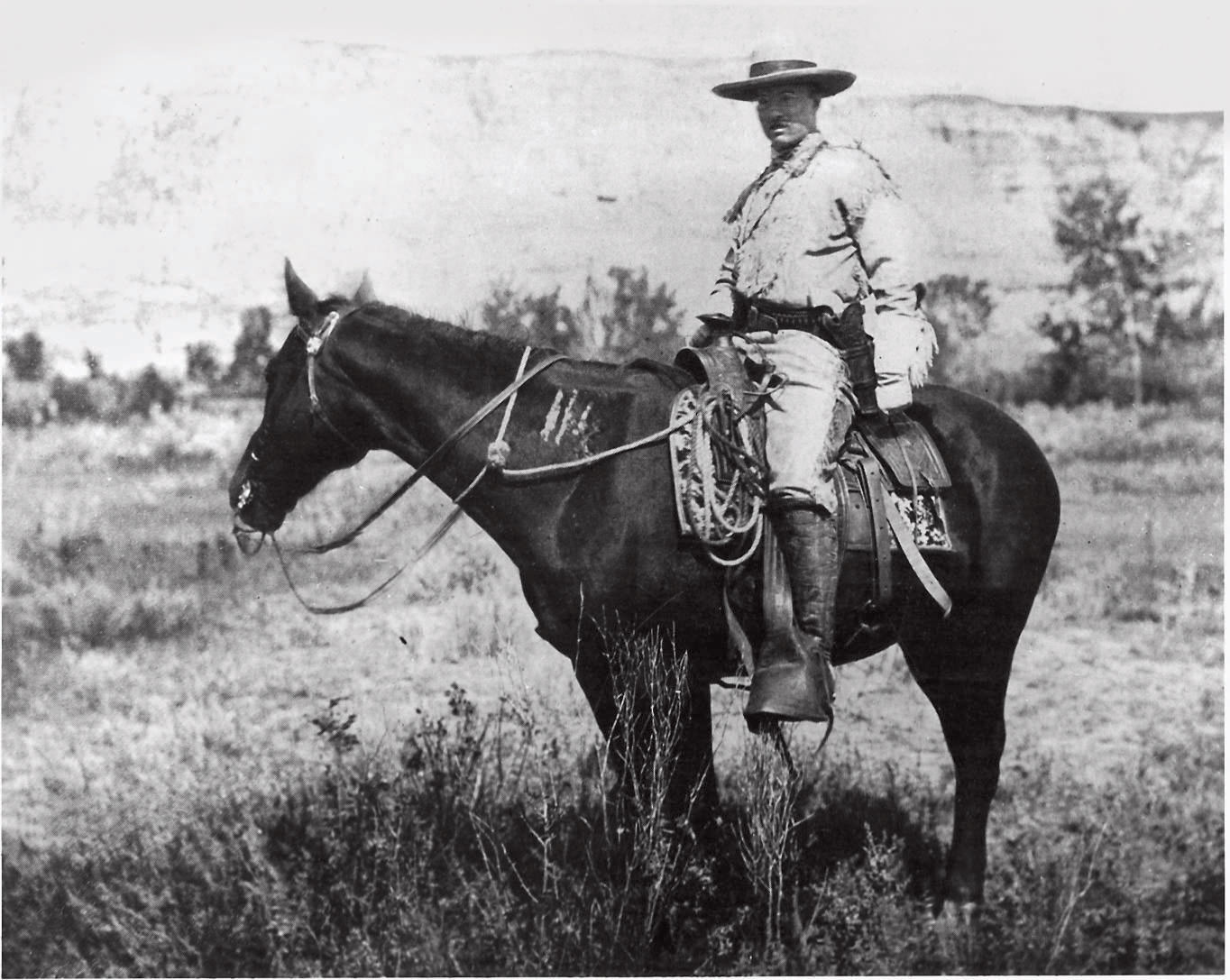

It was September 1883 when a bespectacled 24-year-old Roosevelt, a tenderfoot the locals would call “Four Eyes,” first set foot in the badlands. Born in a brownstone in New York City, he had grown up sickly but privileged, longing since boyhood to experience the rough and tumble frontier for himself. So, as a young man, when the opportunity arose to go on a big game hunting trip and bag one of the last great bison, he left his pregnant wife, Alice, in New York and boarded a train for Little Missouri, Dakota Territory. He couldn’t have known just how much the experience would shape the rest of his life.

Here, on the banks of the Little Missouri River, Roosevelt molded the cowboy image he would use to great effect in his future political career. But there was true transformation beneath the cultivated persona. In the badlands’ harshness and freedom, he discovered a vigorous lifestyle that changed him physically. He learned to ride Western, rope, shoot from the saddle, and hunt, honing skills that would come in handy when he led the cavalry unit known as the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. And he learned a deep reverence for the wilderness, acquiring the heart and determination he would need to become the world’s leading land conservationist.

On that first trip, Roosevelt was on a borrowed horse; this time I am on a new colt. He was hunting adventure; I am paying tribute.

“It was here that the romance of my life began.”

Most visitors come during the high season to enjoy the many glories of summer. The days are reliably warm and the sun is shining. In June, wildflowers are blooming, elk are calving, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park is teeming with wildlife and people. The gateway Old West town of Medora — “North Dakota’s No. 1 vacation” for good reason — opens its hospitable arms to tourists, and there’s plenty to do.

But early fall is the preferred season of my annual pilgrimage. As much as I enjoy the activity of summer, I love the badlands best when the crowds have left and the land returns to its natural, solitary self. In September, the days still warm to the 70s and 80s, but change is in the air. The light begins to soften, the air begins to chill, and the colors begin to blaze. Bull elk let it be known with their loud bugling that rutting season has arrived.

Though elk had almost been hunted out of the region by the late 1800s, Roosevelt still might have heard the resonant bellow of a lone male, futilely seeking a mate. And he could well have experienced the romance of a ride on an autumn day just like this, watching the soft morning light filter through broad cadmium-yellow leaves as they flutter on the gnarled branches of cottonwood trees.

A crispness in the air, laden with sage and juniper, mingles with the musky aroma of leather and horse sweat. Our horses quietly walk through belly-deep grass, perked ears eagerly following the source of a resounding trumpet. We emerge along the lazy muddy waters of the Little Missouri River to find elk calves playfully splashing to the music of the morning while cows wade sedately. A magnificent bull tips his head, white polished tines of his massive rack brushing his rump, and emits that soulful call we have been riding toward. Steamy vapor from his breath reflects the colors of the sunrise. The sight and sound send shivers up my spine.

Roosevelt famously remarked, “The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom.” I know exactly what he’s talking about.

We watch the elk drink their fill of the murky water and then slowly filter back up the wooded draw, their silent, ghostlike travel effortless upon the treacherously steep trail of crumbling rock. As the elk disappear into the trees, the sun breaks over the eastern buttes, brightening the sky to a brilliant blue. A day full of possibility dawns in the badlands. Anything — adventure, healing, transformation, greatness — seems just a ride away.

“I grow very fond of this place, and it certainly has a desolate, grim beauty of its own, that has a curious fascination for me.”

To Native Americans it was Mako Sica, “bad land.” To the Spanish, la tierra baldía, or “the waste land.” To French trappers, les mauvaises terres à traverser, literally “the bad lands to cross.” No matter what this treacherous land has been called, something about it draws people to discover its inner beauty. And in its forbidding splendor and freedom, you come face to face with yourself. This is a soul-proving place. The land itself seems to say, “If you can survive here, if you can survive this, you can survive anything.”

Of course there are more reasons to come here than to face down an existential crisis. Native Americans came here to hunt abundant wildlife. Cowboys driving Texas cattle along long dusty trails came here to graze their herds on the nourishing grasses. A 24-year-old French nobleman, the Marquis de Morès, came here to realize a dream: He arrived in 1883 with the grandiose idea of increasing his fortune in the cattle industry and founded the town of Medora, naming it after his wife, as his base on the Little Missouri River.

And, of course, Roosevelt came here to hunt. Unbeknownst to him, there had been a slaughter of 10,000 bison just the week before his arrival. (He eventually would call their extermination “a veritable tragedy of the animal world.”) Engaging Joe Ferris, a 25-year-old Canadian, as his hunting guide, Roosevelt embarked on a two-week excursion of rough riding by day and cowboy campfire conversations by night. At the end of his 15 days, Roosevelt had his bison — and the respect of his guide, who struggled to keep up with the high-energy Easterner.

Roosevelt also had a new interest in the burgeoning business of ranching. Investing an initial $14,000 in cattle (he would ultimately invest much more), he hired ranch managers Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield to tend them and build him a cabin on the Maltese Cross Ranch. He would eventually have a second cabin on another spread, the Elkhorn Ranch, which he came to regard as his ranch home over the course of future sojourns. (Though the Elkhorn Ranch cabin no longer exists, you can visit the Maltese Cross cabin, which has been moved to Medora, and see the white hutch where Roosevelt wrote about his frontier experiences.)

Roosevelt ultimately lost most of his cattle — and much of his net worth — to the deadly winter of 1886 – 87 that took about 80 percent of the region’s herds, and he returned rarely thereafter. But he was forever enamored of the freedom of ranching and what the Western lifestyle could do for the character. “I do not believe there ever was any life more attractive to a vigorous young fellow than life on a cattle ranch in those days,” Roosevelt wrote. “It was a fine, healthy life, too; it taught a man self-reliance, hardihood, and the value of instant decision. ... I enjoyed the life to the full.”

The experience would prove historic: Becoming a cowboy in the badlands of North Dakota set Roosevelt on a course to become the 26th, and youngest, president of the United States.

I have no such boast, of course. But I can relate, if only modestly. When I rode dear old Al here, I discovered inner reserves I didn’t know I had. I went back to face my final chemo treatment. And I’ve lived to tell the story.

“There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm.”

The rising sun casts a hazy glow on a herd of bison as they amble over the hill to pay a visit to the Roundup Group Horse Camp, where we are gearing up for the day’s ride. Prime velvety coats draped on massive shoulders evidence the ample grass of summer. Voices rumbling in contentment, dust rising under cloven feet, shaggy forelocks gnarled with burrs — the animals are magnificent. And dangerous if you get too close. I keep a safe distance as an amorous bull croons to a cow while a calf licks salty sweat from a halter hanging on the corral.

Horses saddled, we head down the trail. I say “we” as I am, in fact, with friends. Even so, we ride in a perfect awe-inspired silence that lends itself to solitary self-reflection. And to good wildlife viewing — a pastime Roosevelt, a natural-history buff, cherished as much as he loved his hunting.

Riding through a prairie dog town, we startle a bobcat in search of a meal. Black tufted ears flit as he surveys our group then quickly disappears into the brush, tawny spotted coat blending perfectly with the leaves. Equally rare sightings of mountain lions are also a treasured treat on badlands rides.

A band of wild mares grazes near our path as colts sprawl flat on their sides, snoozing in the warm fall sunshine. A black-and-white paint stallion watches as we approach, quietly stepping between his herd and us when we reach his invisible boundary. He stares, dark eyes shaded by a thick forelock that enhances his wild appearance. Inhaling our scent, his nostrils flare. A distinctive hoof print on his flank testifies to past challenges maintaining his herd. Before he disputes our intrusion, we regretfully leave the idyllic scene.

Clear blue sky beckoning, our horses scramble for footing as we climb a scoria-embedded ridge; red shards tumble down the steep slope in our wake. Up on the ridge, I drink in the undulating vista of hills and valleys stretching before me. Far below in a ravine, two bull elk spar, massive antlers rattling as steam rises from their flanks in the chilled air.

Immersed like this in North Dakota nature, it’s easy to feel the great medicine of the place taking effect. I know Roosevelt felt it, too. He needed something strong. After losing Alice, he never spoke of his first wife again, not even to the daughter he named after her. So great was his grief on that Valentine’s Day when both Alice and his mother died that in his journal he simply marked a big black X and wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.” His first life over, Roosevelt returned to the badlands and found another.

With its surface inhospitableness, it might seem an unlikely place for resurrection. But for some of us, it is exactly the right place to rise from the ashes.

I am in that sacred place now. And this is the right moment for my tribute. As a golden eagle soars effortlessly high above the buttes, I place a wreath of Al’s hair entwined with my own at the base of our special rock. My new colt’s mane, blown by the wind, caresses my hands, giving me a sense of the freedom felt beneath the eagle’s widespread wings. I try to imagine the wind in Al’s mane and the freedom he enjoys now as he runs with the angels.

For all I know, Roosevelt paid his own sorrowful tribute. This was his sacred place, too. Here he somehow faced down his pain and determined to live through it. The adventure and romance of the West made him strong and pointed him down a path to greatness. Forging his steel in the cowboy life, he crossed over the badlands and came out the other side a better man.

Following in Roosevelt’s footsteps, I joyfully kick my colt into a gallop toward camp. Fully alive again, my soul has been revived once more.

From the May/June 2011 issue.