The John Ford masterpiece’s nuanced characters and stunning cinematic moments left their marks on the art of film forever.

Back in 1979, long before Kevin Bacon was designated the six-degrees-of-separation center of the pop-culture universe, critic Stuart Byron proposed in a much-discussed New York magazine essay that John Ford’s The Searchers was the primary influence for an entire generation of filmmakers. According to Byron, everything from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) to George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), from Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) to Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979), from Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) to Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), contained thematic and visual elements that could be traced to Ford’s classic drama of obsession and pursuit.

You could argue, of course, that Byron overstated his case. But consider this: Many of the filmmakers who directed films cited by Byron openly acknowledged their debt to Ford’s 1956 classic. Indeed, Steven Spielberg told Byron that he had re-watched The Searchers on location while filming Close Encounters of the Third Kind, for instruction and inspiration. (Spielberg started learning his lessons at a very early age: While he was a seventh-grader in the 1950s, he filmed his own two-reel version of The Searchers in a friend’s backyard, using a backdrop of Ford’s beloved Monument Valley painted on a bedsheet.)

And the beat goes on. Decades after Byron’s article first appeared, the influence of The Searchers has continued to be felt in movies as diverse as Ron Howard’s The Missing (2003), Scott Stewart’s Priest (a 2011 church-versus-vampires thriller that is positively littered with references to Ford’s film), and, most recently, Thomas Bidegain’s Les Cowboys (2015), a well-received French-Belgian drama about a father’s long quest to retrieve a daughter who may have allied herself with Islamic terrorists — and definitely doesn’t want to be found. Even George Lucas can’t let it go: Take another look at Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (2002), and consider Anakin Skywalker’s hunt for his abducted mother. He drops down a cliff and stealthily enters an enemy camp — strikingly similar to activity near the end of Ford’s western.

As Pulitzer Prize-winner Glenn Frankel, author of The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend, told C&I in 2013: “The Searchers is an important film because it played such a formative role in influencing so many contemporary filmmakers. They all saw it while they were in their teens, or really moving up and thinking about making their own movies ... . And that’s been passed on from generation to generation of filmmakers.”

Sixty years after its initial theatrical release, The Searchers still looms large in our collective pop-culture consciousness as one of the truly great American movies, an epic western that expands and transcends the limitations of its genre by offering a darkly powerful counterpoint to the reassuring clichés of standard-issue horse operas. Even after the passing of six decades, Ford’s 1956 masterwork seems fresh and vital as it undermines audience assumptions about what to expect from westerns in general and “a John Wayne movie” in particular.

Wayne gives one of his finest and most complex performances here as Ethan Edwards, a former Confederate soldier who returns to Texas in 1868 after a string of post-Civil War misadventures. (His favorite response to idle threats — “That’ll be the day!” — inspired the signature song of 1950s pop star Buddy Holly.) At first, Ethan is greeted with open arms by his brother, Aaron (Walter Coy), who lives with his family — wife Martha (Dorothy Jordan), son Ben (Robert Lyndon), daughters Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (Lana Wood) — on a remote homestead in an area where Indian raids are common. Gradually, however, long-simmering tensions between the two brothers bubble to the surface. More important, it becomes increasingly clear, to the audience if not to Aaron, that Martha secretly loves her errant brother-in-law.

Ethan’s own feelings are indirectly revealed when, after he returns from a hunt for stolen cattle, he finds Aaron, Martha, and Ben have been massacred — and Lucy and Debbie have been abducted — by marauding Comanches. Fearing a fate worse than death for his nieces, Ethan gives chase, accompanied by Marty (Jeffrey Hunter), a “half-breed” orphan raised to adulthood by Aaron, and Brad (Harry Carey Jr.), Lucy’s boyfriend. Early on, Lucy is found slain, and Brad dies while trying to avenge her. But Ethan and Marty survive to continue their quest for several years — for very different reasons.

Ethan is implacably determined to find his last living blood relative and to save her from becoming the “squaw” of the notorious Chief Scar (Henry Brandon). In most other westerns, Ethan’s obsession would be presented uncritically as a noble endeavor. But in The Searchers, Ford infuses his narrative with a troubling moral ambiguity by repeatedly emphasizing that Ethan is a fanatical racist who rarely hides his contempt for the “half-breed” Marty, and who likely will kill Debbie (played as a teenager by Lana’s big sister, Natalie Wood) if he discovers she has been living as Scar’s wife.

Which is why Marty continues along for the ride: The younger man knows that, if they ever do find Debbie, he may have to kill Ethan to save her.

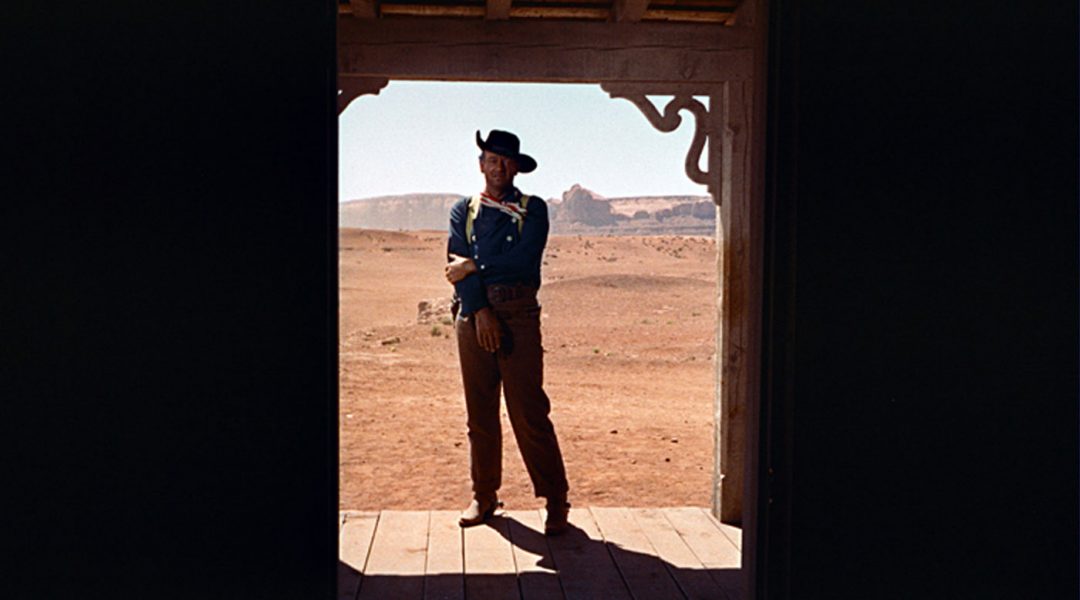

Ford filmed The Searchers in Monument Valley, his location of choice for westerns, and the drama is justly framed for the extraordinary beauty and emotional impact of cinematographer Winton C. Hoch’s widescreen compositions. But two of the film’s most memorable images are intimate, not epic, in scope. In the first, during the opening scenes, a Texas Ranger (played with robust authority by Ward Bond) stands in the dining area of a frontier cabin, drinking a cup of coffee. Quite inadvertently, he spots Martha in the next room as she lovingly embraces Ethan’s military cloak. He quickly averts his eyes — and leaves no room for doubt that he will never reveal what he has seen.

Ethan, the film’s heart of darkness, figures prominently in another unforgettable image. Throughout The Searchers, Wayne gives a performance that is profoundly eloquent as both a concise summation and a skeptical critique of his entire career in westerns. But he is never more affecting than in the closing moments, as Ethan is viewed through the doorway of another cabin, standing alone far away, not quite able to move, while Debbie is warmly welcomed back into civilization. It’s a place, we realize, where Ethan no longer belongs. The door closes. For Ethan, it will never open again.

Stream The Searchers on Amazon video or pick up a special two-disc anniversary edition DVD in stores.

From the November/December 2016 issue.